The Hawaiian Revival

Journey into the 1830s when faith reshaped Hawaii’s spiritual heart and aliʻi embraced a new awakening.

150+

15

Thousands Converted

Faith Renewed

Hawaii Revival –

A Story Of Faith And Transformation

In the early 19th century, the Hawaiian Islands stood at a crossroads of history. Ancient traditions guided daily life, aliʻi (royalty) ruled with sacred authority, and spiritual beliefs were woven into every part of society. Into this world came a small group of missionaries—imperfect, determined, and deeply convicted—whose message would forever change Hawaiʻi’s spiritual and cultural landscape.

A Nation Hinting at Change

Before the missionaries ever arrived, Hawaiʻi was already experiencing profound transition. The kapu system—the ancient religious and social code that governed Hawaiian life—was abolished in 1819 under King Kamehameha II (Liholiho), influenced by Queen Kaʻahumanu and other high-ranking aliʻi. This dramatic decision left a spiritual vacuum across the islands, as the old gods were set aside and the people searched for new meaning.

When the first company of Protestant missionaries arrived in 1820, Hawaiʻi was ready—though no one yet knew how deep the transformation would go.

Queen Kaʻahumanu and the First Printed Bible

Queen Kaʻahumanu, Kuhina Nui (regent) of the Hawaiian Kingdom and one of the most powerful aliʻi in Hawaiian history, played a decisive role in Hawaiʻi’s Christian story. Far from being coerced, Kaʻahumanu actively sought learning, literacy, and spiritual truth.

When the first printed Bibles and Christian texts in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi became available, Kaʻahumanu received them with deep interest and reverence. Literacy was revolutionary—Hawaiians quickly became one of the most literate peoples in the world. Kaʻahumanu understood that access to Scripture in their own language empowered her people, not diminished them.

Her conversion to Christianity was public and transformative. Once a fierce enforcer of the kapu system, she laid down her former authority and openly declared her faith in Jesus Christ. She used her position not to dominate, but to protect missionaries, establish churches, and encourage moral reform rooted in compassion, justice, and aloha.

Keōpūolani: The Highest-Ranking Aliʻi and Her Baptism

Even more striking was the conversion of Keōpūolani, one of the highest-ranking aliʻi in Hawaiian history. By sacred genealogy, Keōpūolani outranked even Kamehameha I. Her kapu was so great that commoners were required to prostrate themselves in her presence, and violations could mean death.

Yet Keōpūolani embraced the message of Jesus Christ with remarkable humility.

In 1823, near her death, Keōpūolani requested Christian instruction, prayer, and water baptism—a radical act for someone of her rank. In choosing baptism, she publicly laid aside the old system of divine separation and declared herself equal before God.

Her baptism marked a turning point in Hawaiian history. If the most kapu aliʻi in the islands could kneel before Jesus Christ, then the Gospel was no longer foreign—it was truly for all people. Her conversion powerfully affirmed that Christianity was not imposed from below or above, but received willingly at the very highest levels of Hawaiian society.

Titus Coan: Revival on Hawaiʻi Island

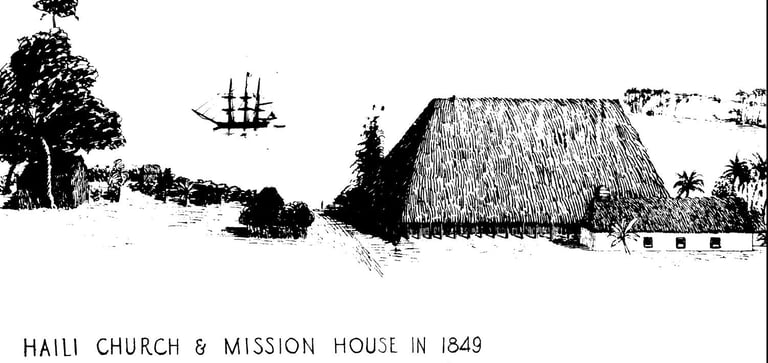

Few figures shaped the spiritual awakening of Hawaiʻi more powerfully than Titus Coan. Arriving in Hilo in 1835, Coan faced resistance, illness, and isolation. Yet he persisted, walking long distances across lava fields, preaching outdoors, and sharing the message of Jesus Christ with humility and passion.

What followed became known as one of the greatest revivals in Pacific history. Thousands gathered to hear the Gospel. Entire communities turned toward Christianity, not through force, but through conviction. Baptisms sometimes numbered in the hundreds in a single day. Coan emphasized repentance, forgiveness, and a personal relationship with Jesus Christ—ideas that resonated deeply with a people seeking spiritual renewal.

David Lyman: Faith Rooted in Education and Family

David Belden Lyman, who arrived in 1832, served for over 50 years in Hawaiʻi. His influence extended beyond the pulpit into education, family life, and community building. Lyman believed that faith must be lived, not merely spoken. He helped establish schools and emphasized literacy so Hawaiians could read the Bible in their own language.

The Lyman family legacy continues today through the Lyman Museum in Hilo, a testament to a life devoted to service, learning, and faith grounded in love rather than control.

Lorenzo Lyons: The Makua Laimana

Known affectionately as Makua Laimana (Father Lyons), Lorenzo Lyons served the people of Waimea for over four decades. Fluent in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, Lyons honored Hawaiian culture while sharing the message of Christ. He is perhaps best remembered for writing the beloved hymn “Hawaiʻi Aloha,” which continues to unite hearts across the islands.

Lyons taught that following Jesus did not mean abandoning Hawaiian identity, but redeeming and restoring what was good through faith, grace, and aloha.

The Conversion of Hawaiian Royalty

One of the most remarkable aspects of Hawaiʻi’s Christian story is the sincere conversion of its royalty. Queen Kaʻahumanu, once a powerful enforcer of the kapu system, became a devoted follower of Jesus Christ. She publicly renounced old religious practices, encouraged Christian teaching, and helped protect missionaries during times of opposition.

King Kamehameha III (Kauikeaouli) was educated by missionaries and embraced Christian principles that later shaped Hawaiʻi’s constitutional government. Under his reign, Hawaiʻi adopted laws influenced by biblical values, including justice, literacy, and human dignity.

Many aliʻi came to see Jesus Christ not as a foreign god, but as a Savior who offered forgiveness, peace, and eternal hope. Their leadership played a crucial role in the widespread acceptance of Christianity among the Hawaiian people.

A Revival, Not a Replacement

While history is complex and not without pain, the spiritual revival in Hawaiʻi cannot be reduced to conquest or coercion alone. For many Hawaiians, Christianity was embraced willingly and deeply. It answered questions of the heart, offered hope beyond death, and aligned with values of love, sacrifice, and community already present in Hawaiian culture.

Churches became centers of learning, music flourished through hymns in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, and the Bible was translated so the people could encounter Scripture in their own language.

Queen Liliʻuokalani, the Overthrow, and the Wound That Followed

To understand Hawaiʻi today, we must speak honestly about a painful chapter.

Queen Liliʻuokalani, a devoted Christian and composer of hymns, ruled during a time of immense foreign pressure. Her imprisonment following the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom was a deep injustice. The loss of sovereignty wounded the Hawaiian soul, and that wound has echoed through generations.

It is true that some descendants of missionaries participated in or benefited from political and economic systems that harmed Hawaiʻi and its people. This reality cannot be ignored or minimized. However, it is equally true that this political overthrow was not the Gospel, nor was it the heart or intent of the missionaries who first came to Hawaiʻi.

Confusing Christianity with colonialism has created a root of bitterness—manifesting in anger, racism, and hatred toward haole and white people—often without a full understanding of the original relationships between Hawaiian aliʻi and the early missionaries.

What History Often Forgets

Long before the overthrow, Hawaiian royalty invited missionaries into the Kingdom. They were not conquerors, soldiers, or rulers. They came at the request and protection of the aliʻi.

Queen Kaʻahumanu, King Kamehameha III, and many high-ranking chiefs openly embraced Christianity because they believed in Jesus Christ—not because they were forced. They studied Scripture, prayed, and governed with values shaped by their faith.

The aliʻi did not see Christianity as an enemy to Hawaiian culture, but as a source of moral strength, literacy, justice, and spiritual renewal. They protected missionaries, learned from them, and in many cases loved them as ʻohana.

Why Baptism Mattered in Hawaiian Context

In traditional Hawaiian society, rank, kapu, and separation defined one’s relationship to others and to the sacred. Aliʻi of the highest rank were set apart—physically, spiritually, and socially. Touch, proximity, and even shared space were regulated by kapu, with life-and-death consequences.

Christian water baptism carried profound meaning in this context.

When Keōpūolani and other aliʻi chose baptism, they were not adopting a foreign ritual lightly. They were making a radical declaration: that before the God of the Bible, all people—aliʻi and makaʻāinana alike—stand equal in need of grace. Baptism symbolized cleansing, humility, and new life, but in Hawaiʻi it also represented the laying down of inherited spiritual separation.

This was not loss of dignity. It was a redefinition of power—authority rooted not in fear, but in love.

A Timeline of Faith Among the Aliʻi

• 1819 – The kapu system is abolished under Kamehameha II, guided by Kaʻahumanu and other aliʻi, signaling a nation in spiritual transition.

• 1820 – The first Protestant missionaries arrive, welcomed and protected by Hawaiian leadership.

• 1823 – Keōpūolani, the highest-ranking aliʻi by genealogy, receives Christian instruction and water baptism before her death.

• 1825–1832 – Queen Kaʻahumanu publicly converts to Christianity, promotes literacy, and encourages Christian teaching across the Kingdom.

• 1839–1840 – King Kamehameha III proclaims religious freedom and establishes a constitutional government influenced by Christian ethics.

• Late 1800s – Queen Liliʻuokalani, a committed Christian, composes hymns, prays openly, and models forgiveness even during imprisonment.

This was not a fringe movement. Christianity took root at the very center of Hawaiian leadership.

Responding to the Claim: “Christianity = Colonialism”

This statement, often repeated, oversimplifies a complex history.

Colonialism involves conquest, coercion, and control. The early Christian movement in Hawaiʻi began instead with invitation, relationship, and consent. Missionaries did not arrive with armies or political power. They arrived dependent on the goodwill and protection of the aliʻi.

Political and economic exploitation came later, driven largely by global imperial forces and business interests

Our Services

Dive into the stories and artifacts of Hawaii's spiritual revival.

Guided Tours

Walk through sacred sites where history and faith intertwine.

Exhibit Access

Explore rare relics and stories from the 1830s awakening.

Experience the spirit of aloha through immersive cultural events.

Cultural Events

Awakening

Moments from Hawaii’s profound spiritual transformation.

Get in Touch

Questions or stories? We'd love to hear from you.